In this article, I will share the historical multicultural roots of the real first Thanksgiving, challenging and enriching our traditional understanding.

Join me on a journey to explore the diverse histories that shape the Thanksgiving we celebrate today.

Debunking “The Real Thanksgiving” Myth

For many, the story of the Pilgrims at Plymouth Colony represents “the real Thanksgiving,” a narrative deeply rooted in American culture and history.

This tale, often encapsulated by iconic images of Plymouth Rock, has been passed down through generations, forming a cornerstone of the Thanksgiving story as we know it today.

However, a closer look at real history reveals a more complex and perhaps less known version of events. The traditional narrative, centred around Plymouth and its settlers, only tells part of the story behind Thanksgiving.

In contrast, the Spanish Thanksgiving in St. Augustine, Florida, presents a compelling alternative that challenges our conventional understanding and invites us to explore the true story of America’s actual first Thanksgiving.

The more we go deeper into this debate the more we find the narrative that not only predates the Plymouth celebration but also enriches our understanding of this beloved holiday.

The Setting of the Spanish Thanksgiving and Native Peoples

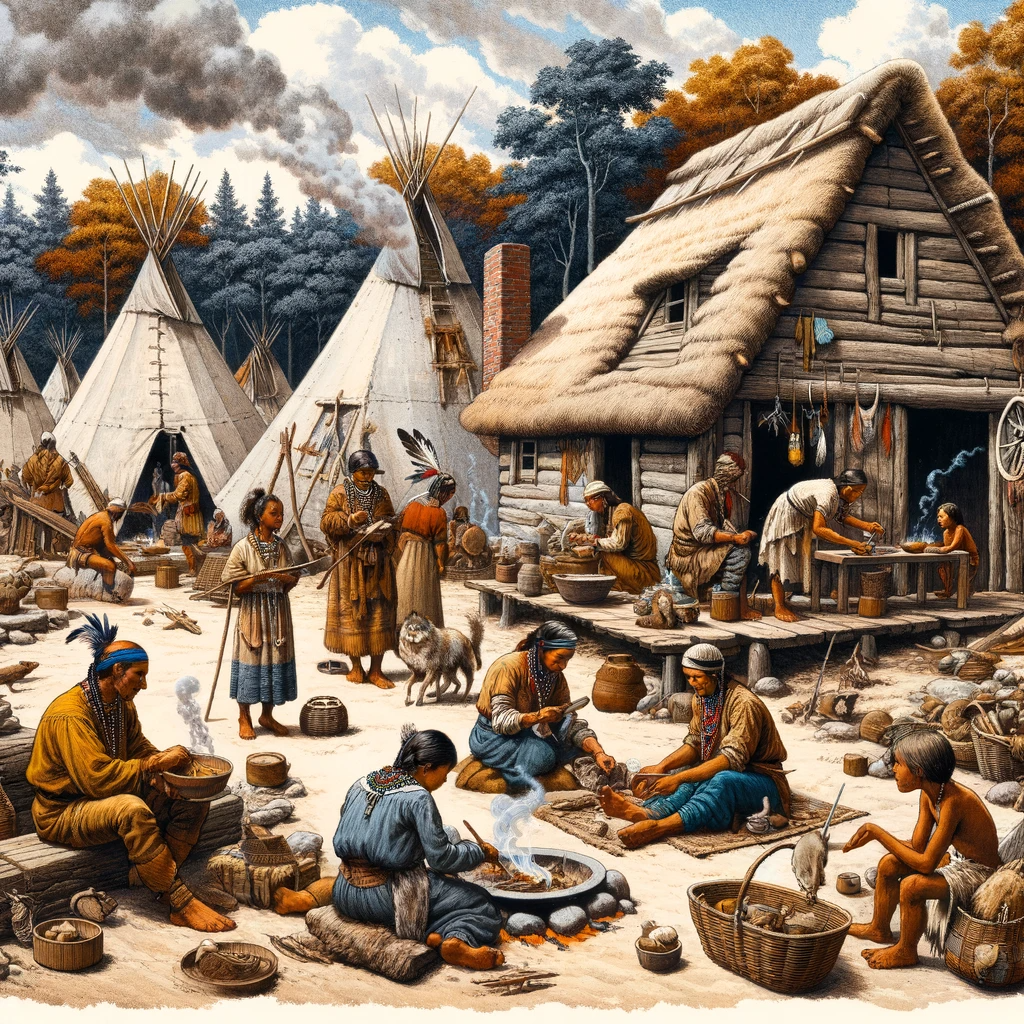

In the beginning of the 16th century, European settlers ventured into the New World, an era marked by exploration and encounters with native tribes. This period dramatically changed the lives of native communities, who faced new challenges and transformations due to the arrival of Europeans.

At the heart of this era was Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, a figure central to the story of the Spanish Thanksgiving. Menéndez, unlike many European colonists of his time, is noted for his unique approach to dealing with indigenous peoples.

Building Bridges Between Two Worlds

Menéndez was not just an explorer but also a bridge between two worlds. His interactions with native population were marked by efforts to understand and engage with their cultures.

Which was uncommon during a time when many European explorers often disregarded the spiritual connection and customs of the native communities they encountered.

In St. Augustine, Menéndez’s arrival signified more than just a claim to new land; it marked the beginning of a complex relationship between European colonists and indigenous peoples.

This period in history is pivotal, not only for its historical significance in the colonization of the Americas but also for its impact on the indigenous history and cultures that existed long before the European arrival.

Setting the Stage for the 1565 Feast

As we move deeper into the setting of the Spanish Thanksgiving, it becomes evident that this event was not an isolated celebration but a part of a larger narrative involving diverse cultures and histories converging in the New World.

This includes the cultural interactions occurring further north in Cape Cod, which were integral to early settler history.

As Menéndez and his crew settled into their new environment, their interactions with the Timucua tribe began to shape a unique chapter in history.

This period of exchange laid the groundwork for what would become a remarkable event in 1565 — a feast that symbolized mutual respect and a melding of cultures, setting the stage for a Thanksgiving that precedes the well-known Plymouth celebration.

The 1565 Feast: Honoring Native Ancestors in St. Augustine

Building upon this foundation of cultural exchange, the 1565 feast in St. Augustine emerged as a poignant moment in history. Not only a mere sharing of meals, it was a profound gesture of respect and mourning for the native ancestors.

This first Thanksgiving, a collaborative celebration between the Spanish and english settlers and the Timucua tribe, marked a significant departure from the typical harvest feast narratives.

On this notable day, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, leading the Spanish settlers, joined the Timucua tribe in a Thanksgiving celebration. The gathering was more than a meal; it was a celebratory feast symbolizing cooperation and mutual respect between two very different cultures.

The Spaniards, recognizing the importance of the native ancestors’ contributions to their survival and understanding of the land, shared a meal that represented a blend of two worlds coming together.

A Feast That Honors Legacy and Hope

The menu of this first Thanksgiving contrasted with the traditional harvest celebrations later known in New England. It included local produce and foods native to the region, showcasing the richness of the land and the bounty it provided.

This meal, shared in the spirit of gratitude and respect, honoured the native ancestors and their enduring legacy.

This 1565 feast in St. Augustine stands as a poignant reminder of the diverse histories that contribute to our understanding of Thanksgiving.

It was a moment where mourning for past conflicts and losses intertwined with hope for a future built on mutual respect and cooperation between native peoples and European settlers.

Historical Comparison: St. Augustine vs. Wampanoag Tribe and Pilgrims

Following the 1565 feast in St. Augustine, a different narrative unfolds over half a century later in the north, at the Plymouth Colony. Here, the Pilgrims, having arrived in the New World, held a celebration that has traditionally been recognized as the first Thanksgiving.

This event involved the Wampanoag tribe, a moment often portrayed as a peaceful and harmonious gathering. Yet, the nuances and complexities of this interaction are worth exploring in contrast to the earlier St. Augustine Thanksgiving.

The St. Augustine feast with the Timucua tribe and the Plymouth celebration with the Wampanoag people present two different models of early Native American and European settler relations. In St. Augustine, the interaction was notably marked by a sense of mutual respect and cooperation.

The Spanish settlers recognized the value and importance of the native people, integrating their customs and foods into the celebration. This event stands as a testament to shared respect and an acknowledgement of the native ancestors.

The Wampanoag Tribe and Pilgrims at Plymouth

In contrast, the Plymouth celebration, while often romanticised as a similar meeting of cultures, carried different undertones. The Wampanoag tribe’s involvement with the Pilgrims was complex, shaped by necessity and mutual benefit in the face of challenges.

However, over time, this relationship grew strained, leading to conflicts and a significant alteration in the way of life for the Wampanoag people. The national day of mourning observed by some Native Americans today serves as a reminder of these subsequent hardships and conflicts.

Both events – in St. Augustine and Plymouth – represent critical moments in history, each illustrating a different facet of the early encounters between Native Americans and European settlers. Understanding these events helps us appreciate the diverse experiences and perspectives of the two groups involved, offering a more nuanced view of the early years of European settlement in America.

Also Read: 45+ Fun Things to Do on Thanksgiving Day

How Is Black Friday Linked with Thanksgiving?

Black Friday happens the day after Thanksgiving and it’s when Christmas shopping starts in the United States. It’s a really busy shopping day with lots of sales and stores opening early. The name “Black Friday” wasn’t always about shopping.

It used to be what people called the day when lots of workers would take a sick day after Thanksgiving. It also reminds people of a big problem with money that happened back in 1869.

For shops, Black Friday is important because they start making more money from all the things they sell. This change from Thanksgiving, which is about being thankful and spending time with family, to Black Friday, with its big sales and shopping, shows how American holidays can have different meanings.

It’s like having two sides of the same coin – one is about history and family, and the other is about buying things and deals.

Legacy and Recognition: Mourning and Honoring Native Ancestors

The historical oversight of the Spanish Thanksgiving in St. Augustine reflects a broader trend in how we remember and honour the past. This event, though significant, has often been overshadowed by the more widely recognized Pilgrim feast in Plymouth.

This oversight is not just a matter of missing a page in history; it represents a gap in our collective understanding of the full story and the true history of Thanksgiving in America.

In recognizing the St. Augustine feast as a pivotal part of the Thanksgiving narrative, we also acknowledge the deeper need to honour the contributions of Native Americans to American history.

Their role and impact extend far beyond being mere participants in a celebratory meal. Native Americans have been instrumental in shaping the country from its earliest days, yet their stories and sacrifices have often been marginalised or overlooked.

A National Day of Mourning and Reflection

The national day of mourning, observed by many Native communities, coincides with the national Thanksgiving Day.

This day serves as a poignant reminder of the losses and struggles Native Americans have endured since European settlers arrived. It invites us to reflect on the past with a sense of mourning, respect, and acknowledgement of the true complexities of American history.

As Thanksgiving has evolved into a national holiday, it’s essential to embrace this opportunity to not only celebrate but also to reflect on the diverse narratives that make up our national story.

Recognising the legacy of Native Americans and honouring their ancestors is a crucial step in building a more inclusive and truthful understanding of Thanksgiving and its origins.

Notably, the designation of Thanksgiving as a national holiday by Abraham Lincoln further solidified its place in the American cultural and historical landscape.

Reinterpreting Thanksgiving: Inclusive Narratives and Native Perspectives

As our understanding of history evolves, so does our interpretation of Thanksgiving.

Modern perspectives on this holiday increasingly highlight the contributions of Native Americans, shifting from a singular narrative to a more inclusive and comprehensive view.

This shift is crucial in a country and world where multicultural histories are intertwined and where every voice adds to the richness of our shared story.

Native American Contributions and Advocacy

The ongoing contributions of Native Americans continue to shape not just the holiday but the fabric of the nation itself.

Groups like the United American Indians have been instrumental in bringing these perspectives to the forefront, advocating for a more accurate and respectful representation of history.

Their efforts remind us that the story of Thanksgiving, and indeed the history of the United States, is not a single narrative but a tapestry woven from many diverse threads.

Embracing Reflection and Multiplicity of Narratives

In this context, reevaluating the meaning of “the real Thanksgiving” becomes an exercise in recognising the multiplicity of experiences and perspectives that make up our past.

It’s about understanding Thanksgiving not just as a time for celebration but also as an opportunity for reflection and learning.

By embracing the various narratives of Native peoples, along with those of the European settlers, we gain a more nuanced and truthful understanding of our history and its impact.

Embracing a Multicultural Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is more than just a holiday; it’s a reflection of America’s rich and varied history. Recognising the Spanish Thanksgiving in St. Augustine and the vital role of Native Americans gives us a fuller understanding of the holiday’s origins.

It’s important to appreciate all the narratives that contribute to Thanksgiving, from the well-known story at Plymouth to the lesser-known but equally significant events in Florida.

Embracing this diversity helps us see Thanksgiving not just as a day for feasting, but as an opportunity to celebrate and learn from the many cultures that shape our nation. As we gather each year, let’s remember and honour the full spectrum of stories that make up our shared history.

What was the real Thanksgiving food?

The real Thanksgiving food in St. Augustine, 1565, likely included Spanish and local Timucuan dishes like salted pork, garbanzo bean stew, sea biscuits, and native foods such as oysters, fish, and possibly turkey.

Did Christopher Columbus create Thanksgiving?

No, Christopher Columbus did not create Thanksgiving. The holiday’s origins are more closely tied to various harvest celebrations and feasts held by European settlers and Native Americans, including the Spanish in St. Augustine and the Pilgrims in Plymouth.

How many natives were killed on Thanksgiving?

There’s no specific record of natives being killed on Thanksgiving itself. The holiday’s history, while intertwined with European-Native American interactions, doesn’t specifically detail violence on the day of Thanksgiving celebrations in its early observances.